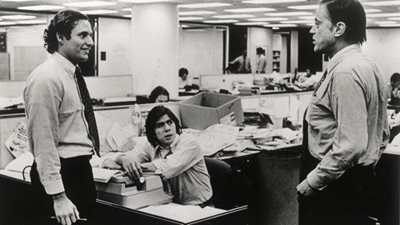

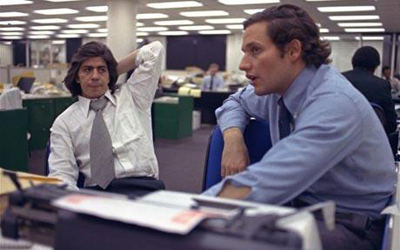

Interview: Peter Hossli

Carl Bernstein: A good story is something that fascinates people, raises questions, and answers them.

Wasn’t Watergate about much more than that?

With Watergate, we are talking about the president of the United States, the most powerful individual in the world, who in the instance of Richard Nixon committed grave and egregious constitutional crimes and related criminal acts. But then, the American system worked. The press did its job, the judiciary did its job, and Congress did its job, and a president of the United States was forced to resign his office.

When did you realize that it was also an important story?

Right away. The original burglary was something extraordinary that almost certainly had to have high governmental involvement.

The White House characterized Watergate as a “third-rate burglary”.

It’s very important to recognize that Watergate was not simply about the break-in at the Democratic headquarters. It was a massive campaign of political espionage and sabotage directed by the president, intended to undermine the most precious of all American freedoms, which is free elections.

This was a once-in-a-lifetime story. What kind of rush or kick did you get out of it as a reporter?

When we found out that there was a secret fund that paid not only for the bugging at Watergate but for other undercover activities, and that that fund had been controlled by the two or three people closest to Richard Nixon, I felt this incredible chill go down my spine such as I never felt. And I turned to Woodward and I said, “Oh my God, this president is gonna be impeached.” And Woodward said to me, “Oh my God, you’re right. And we can never use that word ‘impeach’ in this newspaper office because somebody will mistake it for thinking we have an ax to grind.”

A lot of life is overcoming fear. I think it’s perhaps easier when you’re 28, 29 years old. But also, we had the incredible and enormous backing of this great institution, a very powerful institution, The Washington Post, with Ben Bradlee and Katharine Graham behind us, which gave us a great sense of comfort.

Their backing eliminated fear?

No, our greatest fear became that we would make a mistake.

What was it like to go through the Watergate experience?

It’s a little bit like getting in a hot bath. The temperature wasn’t scalding when we got into it. Gradually it became hotter and hotter, but we had adjusted to that increase in temperature. Reporters like a good story, and this was a great story, whatever the fear and danger were.

Europeans think of U.S. reporters as being more fearless. Why is that?

We have a tradition in the United States of great journalistic institutions committed to the idea that their function is to give readers and viewers the best obtainable version of the truth. That’s really what good journalism is: the best obtainable version of the truth.

In Europe that tradition was never as strong, partly because so many newspapers and journals started as voices for one party or ideological movement or another.

How important was the contribution of Mark Felt, known as “Deep Throat”?

The whole Deep Throat mythology has become perhaps inevitably overblown and exaggerated. There are only about half a dozen times that Woodward met with Deep Throat, and a few phone calls during the course of Watergate. Only on a few of those occasions did he volunteer original information. Rather, he confirmed things we had obtained elsewhere.

Still, even today Deep Throat remains the source of all sources.

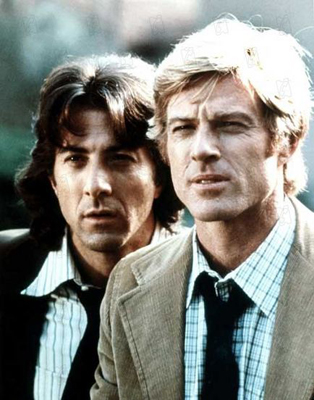

Two things happened. Even though it’s very accurate, the movie All the President’s Men gave dramatic immediacy to the Deep Throat meetings that were perhaps more prominent than they were. Secondly, this secret was unlike any other secret, because only four people knew who Deep Throat was — myself, Woodward, Ben Bradlee, and Felt — and there were half a dozen books written about who Deep Throat is. There were whole semesters in journalism school in which really stupidly unthinking professors assigned their students whole semesters to try and unravel who Deep Throat was.

We perhaps can never know all of the reasons. But he certainly believed that the president of the United States was — and the people around him were — engaged in criminal acts. Second, he was angered at not being made director of the FBI and was particularly angry that the FBI investigation under the man who was named director, Pat Gray, was compromised.

Your work after Watergate was always compared to Watergate. In what way has it become a burden for you — or for Woodward?

This is kind of popular journalistic nonsense that it’s a burden. Both Bob and I have continued to explore the themes that we developed in Watergate, which is the use and abuse of power.

Still, nothing has come close to Watergate.

A story such as Watergate has only happened once in our lifetimes. You absorb the lessons, and you try to apply them to the rest of your work and the rest of your life.

You and Woodward separated professionally after Watergate. Why?

There were some disagreements, and we each were looking for a little space from the other. There was a period of some estrangement, not total estrangement, for a year or two after in the late ’70s.

And today?

We’re closer now, probably, than we’ve ever been. We’re on the phone with each other a couple times a week; we’re e-mailing each other constantly. This has been the case for many years now. This year we’ve even done a dozen speeches together. We’re writing a piece, actually, on the 40th anniversary of Watergate for The Washington Post. So you’re thrown together like this before you’re 30 years old. It’s a bond like no other that we share, and it’s a source of great joy and strength for both of us.

Looking back 40 years, how has Watergate changed journalism?

It reconfirmed that the basics of reporting is to get the best obtainable version of the truth.

By knocking on a lot of doors, wearing out shoe leather, having great editors and publishers, and producing the stories one at a time with space in between to think about context and to have the luxury of two people working on a story together, of getting multiple confirmations of sources — secondary, two sources at least.

Did Watergate have any bad effects on journalism?

Too many would-be journalists and some legitimate ones got it into their heads that the purpose of journalism is to catch crooks or to manufacture controversy. The increasing dominance of manufactured controversy, lack of context, gossip, and sensationalism is overwhelming the best obtainable version of the truth.

Today, reporters investigate with Google, Facebook, and Twitter. What does this mean for journalism?

Social media has a real place in allowing people at the scene of events both through video and written observation to make some important reportorial contributions. But that’s hardly the same as real reporters, real journalistic institutions with real standards of the best obtainable version of the truth being the bottom line — not ideological commitment, not trying to bring about a political or religious result.

How would you rate the quality of today’s investigative journalism?

There’s some fabulous reporting being done, especially in the United States. But by and large, the overwhelming media equation today is speed rather than accuracy and context.

The reputation of the U.S. press suffered, particularly during the Bush years.

You can’t blame the press for the war in Iraq. But there was too much willingness in the press to accept the pronouncements of the president, and of the men and women around him, as truthful, when in fact it wasn’t. There was a laziness that was prevalent. At the same time, the press was quite quick to begin to understand what this presidency had led us into once the war had begun.

Who’s to blame?

You can’t separate media from the rest of the culture itself, and I think the idea that only journalists are to blame for this is wrong. Consumers of so much garbage that masquerades as journalism, they’re equally to blame — that more and more people are reading to reinforce their own prejudices and opinions and preconceived notions and ideologies and religious beliefs and prejudices than they are interested in finding out what’s really true and real.

Can newspapers survive?

I’m not too worried about newspapers in the print format surviving or flourishing. I think that the Web is a great reportorial platform. We need better economic models, so that journalistic institutions can make money on the Web.

Don’t we have the Internet to blame for the decline of newspapers?

It perpetuates a great myth to say that all this came about as a consequence of the Internet. It did not. Our newspapers were in deep trouble, many of them, before the Internet became a major factor.

With the conglomeratization of so much of the American press. Gannett bought up first-rate newspapers in communities all around the country and stripped them bare and took away their reporting budgets and left them a shell of themselves and a local disgrace. The Gannett people — and those like them — are every bit as responsible for the decline as people like Murdoch.

If you were a young reporter today, for whom would you like to work?

The greatest newspaper or journalistic institution in the world today is unquestionably The New York Times. It puts out probably the best newspaper that’s ever been produced that reflects both the modern technology and modern realities, and yet remains committed to the best obtainable version of the truth.

What makes a great newspaper?

The idea that newspapers or journalistic institutions have to be dull is nonsense. Good newspapers were always sources of wonderful entertainment, while at the same time being committed to the best obtainable version of the truth. And The Times continues that with great cultural coverage, with great style covering.

What about The Washington Post?

It still does some great reporting, still has a commitment to investigative reporting. At the same time, it is a shrunken institution in terms of the number of editorial employees. It has no foreign bureaus at this point. It’s redefining itself, so it’s no longer in the same category as The New York Times.

Why couldn’t it use Watergate to expand?

The Washington Post company made some bad choices after Watergate. Bob and I had hoped that the paper would have built on what it did in the Pentagon Papers and Watergate and become more a national news institution instead of focusing on its role as a Washington newspaper. It could have competed successfully against The Times, but it chose not to. That was a big mistake.

Why did you leave The Post in 1977?

It was a period when Bob and I weren’t getting along particularly well. I was not challenged by the idea of daily journalism. I wanted to do long-form reporting. I did a 25,000-word piece for Rolling Stone on the CIA and the press, and then I went into television for a little while.

I don’t know if it’s courageous. It’s more indicative of who each of us is. But the amazing thing is the respect, affection, bond that we have and that both of us look at the other’s work, I think, as a real recommitment to those things that we found count in terms of what reporting is in Watergate.

What do you think of Richard Nixon today?

Nixon was preoccupied with revenge against people and institutions that he perceived as his political enemies, rather than being preoccupied with the national interest.

But you and Woodward owe your stature to him.

Obviously, there’s a connection there. Nixon, Woodward, Bernstein are gonna be inextricably bound through circumstance long after we’re all gone.

He will be in your first paragraph of your obituary.

That’s inevitable, and it’s just fine.